Is Japan The Root Cause Of The Current Sell-Off In U.S. Treasuries?

The Simplest Answer Is Usually The Right One

For the better part of the past four months, long-term Treasury yields have been moving steadily higher. A resiliently strong U.S. economy, a progressively more hawkish Fed and the emergence of a new potential inflation threat have all worked together to push the 10-year yield more than 100 basis points higher in pretty short order.

But what if there’s another catalyst at play?

The trio of catalysts I just laid out do a pretty good job of explaining the behavior in the Treasury market, so there hasn’t been much need to search for alternative or additional explanations. But there’s one thing that I've been thinking about. Even when inflation was topping 9%, the 10-year yield only topped out at 5% (and that was about a year after that rate was hit). Why is the 10-year yield approaching that level again today even though the inflation rate is only 2.7%?

Of course, long-term yields aren’t directly tied to Fed policy, so it’s not meant to move in lockstep with the Fed Funds rate. But isn’t the 10-year yield probably still getting a little too high here, especially considering a lot of people still don’t think that a second round of inflation has yet to become an issue?

Is it because this is the doing of the Bank of Japan?

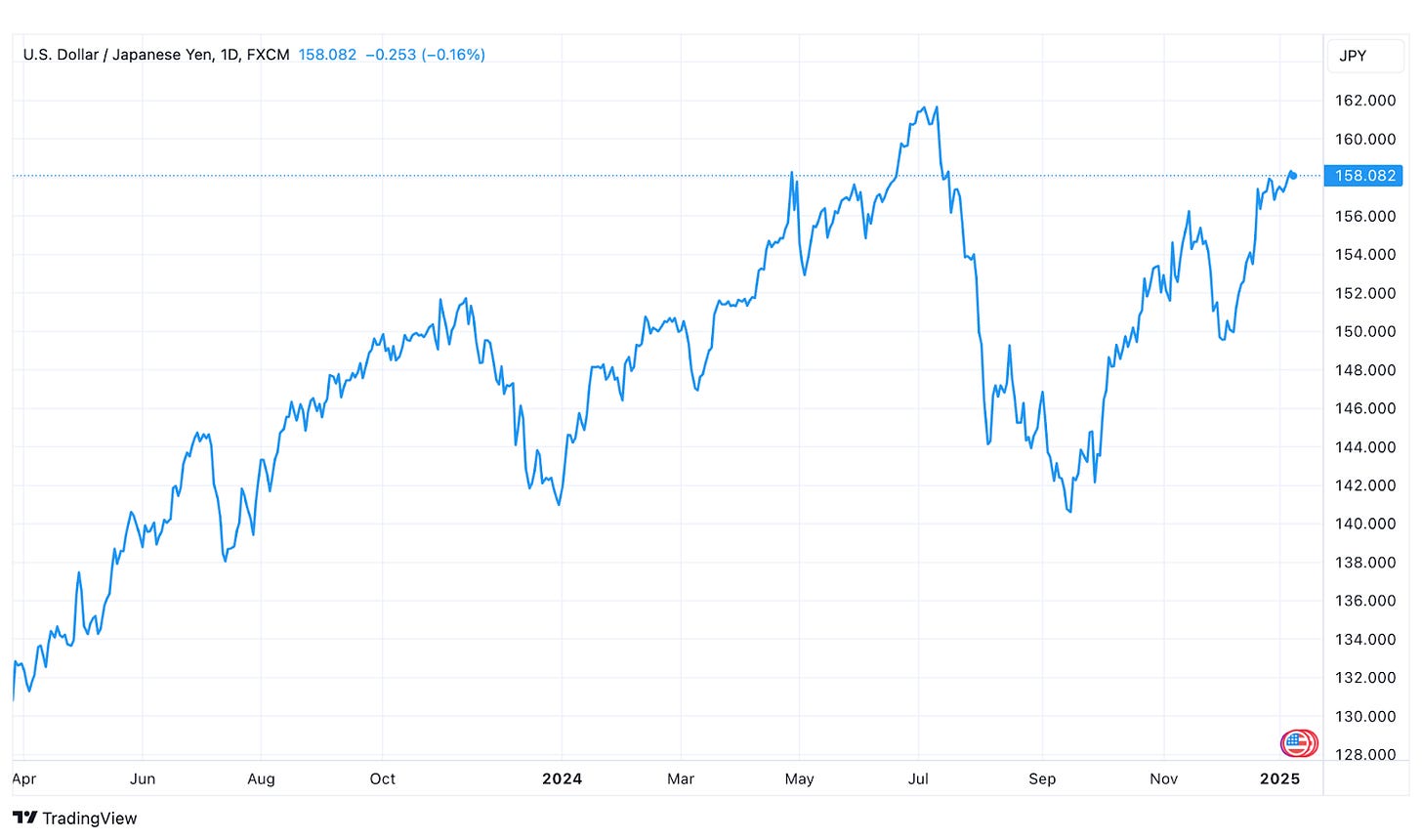

Let’s consider what we think we know here. After the big yen carry trade unwind that sent the currency soaring and spiked the VIX in the process, it’s gotten consistently weaker, moving nearly in lockstep with the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield.

Of course, that’s not surprising given how yields are tied to the dollar, but it’s the fact that it’s gotten all the way back to 158 that’s notable. Historically, the Bank of Japan has been inclined to consider yen intervention around the 150 level. That’s traditionally been a soft cap for the yen because the market believed the BoJ would step in around that level to support it. In several cases, they’ve been right.

In 2024, however, they let the yen trade through that level. They made a couple of interventions, which strengthened the yen only temporarily, before it started weakening again. Perhaps sensing these interventions to be a waste of money, they held off on doing it again.

The only thing that really worked to save the yen was a rate hike from the Bank of Japan. In fact, it worked too well. The yen went from 161 to 141 over the course of a couple months, upended the forex market, resulted in a global equity pullback and sent the VIX to historically high levels. But after a strong month-long rally, it happened again. The yen started weakening and it’s now nearly back to the level it was just prior to the BoJ’s last rate hike.

Special Announcement

Mind the gap!

A substantial, oft-unnoticed gap currently exists in the center of the typical equity allocation. Running Oak's Efficient Growth strategy fills that hole like few do, providing significant value like even fewer do.

Why Invest in Efficient Growth:

Top 2-3 percentile: Running Oak’s Efficient Growth separate account has performed in the top 2 to 3% of all Mid Cap core funds in Morningstar's database over the last 10 years, net of fees.1

Since inception, Efficient Growth has provided 26% more return than the S&P 500 Equal Weight Index and 69% more return than the Russell Mid Cap Index, given the same level of downside risk, gross of fees. (Ulcer Performance Index) 1

Outperforming | Opportune – Mid Cap

The standard equity allocation leaves a large gap in upper Mid, lower Large Cap.2

Mid Cap companies have outperformed Large Cap by 0.54%, annualized, over the last roughly 33 years and outperformed Small by 1.85%.3

Mid Cap stocks are roughly 10% undervalued, per the asset class's CAPE ratio. Large Cap is overvalued by 50 to 100%, depending upon the source. 4

How to Invest

Efficient Growth is currently available as an SMA and ETF. (ETF specifics and audited historical performance can't be shared in the same note. Please reach out for the ticker or more information at seth@runningoak.com.)

In just 18 months, The ETF Which Shall Not Be Named has grown over 13,000% since launch – from 2 to 270mm.

All opinions expressed in this newsletter are those of Running Oak Capital’s and do not constitute investment advice.

1For additional data and context regarding the claims made within this email, please refer to the Disclosures and Additional Data document located here.

2Statements on the standard equity allocation are based on informal feedback and experience from interactions with investors and other financial professionals.

3Invesco: "Why Mid Caps Now"

4Ned Davis Research

Investment Advisory Services are offered through Running Oak Capital, a registered investment adviser.

*Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Performance expectations are no guarantee of future results; they reflect educated guesses that may or may not come to fruition. All indices are unmanaged and may not be invested into directly.

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index is a capitalization weighted index of 500 stocks designed to measure performance of the broad domestic economy through changes in the aggregate market value of 500 stocks representing all major industries.

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investments and strategies may be appropriate for you, consult with us at Running Oak Capital or another trusted investment adviser.

Statements on the standard equity allocation are based on informal feedback and experience from interactions with investors and other financial professionals.

Stock prices and index returns provided by Standard & Poor’s.

DISCLAIMER – PLEASE READ: This is sponsored advertising content for which Lead-Lag Publishing, LLC has been paid a fee. The information provided in the link is solely the creation of Running Oak. Lead-Lag Publishing, LLC does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information provided in the link or make any representation as to its quality. All statements and expressions provided in the link are the sole opinion of Running Oak and Lead-Lag Publishing, LLC expressly disclaims any responsibility for action taken in connection with the information provided in the link.

Now the BoJ is stuck. Last month, they decided to punt on a rate hike, opting instead to wait for more data that would confirm the inflationary trend before acting. Hours after they held on rates, Japan reported that the annualized inflation rate jumped from 2.3% to 2.9% in November. Oof! Wage growth is also on the rise, but it seems that even a January hike is not nearly a done deal. Sounding more dovish, Governor Ueda sounds inclined to punt again until March, citing concerns about unknown Trump policies and wanting more wage data information. Translation: the pressure could be on the yen to get weaker still.

Unless there’s some sort of intervention!

Maybe the BoJ isn’t showing urgency to hike because they have another yen intervention in the works. But there’s an issue with this. The BoJ can’t make a huge yen purchase unless they have the funds to do it. Where are they going to get those funds? How about selling their Treasury holdings?

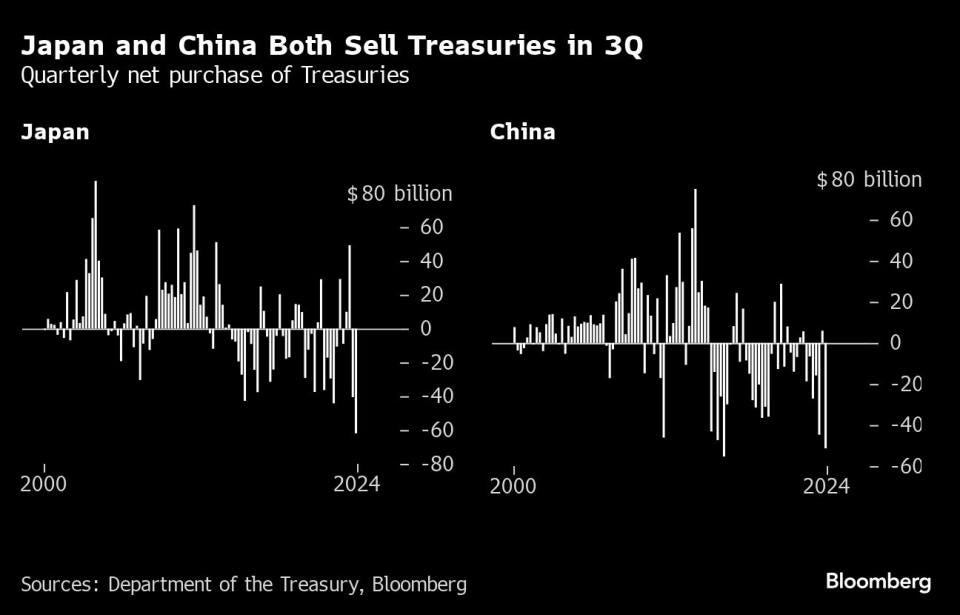

There’s data to back this up. Japan just completed two of their largest quarterly net sales of U.S. Treasuries of at least the past quarter century.

While there’s no way to directly tie the sale of its U.S. Treasury holdings to a yen intervention, it makes sense if you connect the dots. Would it be effective? It’s hard to say since the two known interventions the BoJ executed in 2024 yielded almost no results. But there’s one thing we do know….

They’re thinking about it!

It seems abundantly clear that if the BoJ really wants to strengthen the yen here, a rate hike would be the way to go. It would almost certainly be more effective and wouldn’t cost billions of dollars to do it. The downside, of course, is that it creates tighter monetary conditions that would be felt economy-wide (although a quarter-point move likely wouldn’t be a game changer and even then it likely wouldn’t be felt for 12 months). Perhaps the BoJ feels flexibility within policy conditions is more important even if a yen intervention comes at a significant cost and has a questionable impact.

Regardless of which path the BoJ chooses, it seems likely they’re going to panic. The reverse yen carry trade isn’t over. And it could be the catalyst that finally triggers a global credit event.