The markets got an extra bit of volatility on Monday when President-elect Trump’s tariff policy may (or may not) have come into focus. At issue was a Washington Post report saying that the administration was considering blanket tariffs on products from only certain key industries as opposed to blanket tariffs on all imports. The softer tone on foreign trade would certainly be positive at the margins for consumers as it would limit some of the threat of inflation, although Trump has denied that such a policy is being considered.

Trump himself has acknowledged that he can’t guarantee that his original blanket tariff policy wouldn’t increase inflation, so I believe a more limited policy is indeed at least under consideration. I believe Trump views tariffs as a negotiating ploy or a means of getting what he wants politically. The “will he, won’t he” rhetoric goes back to the days of his first term when any mention of tariffs would move the markets. In the end, a relatively limited degree of tariffs were ever implemented and it didn’t end up having a meaningful impact on inflation or trade. I think Trump’s broad tariff threat fulfills his “America First” tone that he’s maintained throughout the past decade, but I also think he realizes that it is economically dangerous and threatens to alienate many of his supporters. In the end, I think there’s a good chance we see a much more modest tariff implementation that ultimately eases some long-term pressures.

The JOLTS report this week, which usually serves as a precursor to the Friday non-farm payroll report, continues to show a labor market that’s mixed. On one hand, the job openings figure rose to more than 8 million for the first time since May, indicating healthy demand for workers. On the flip side, non-farm hires hit their lowest level in 8 years (excluding the COVID era plunge) and continues a 3-year trend of slower hiring. The quits rate and number of quits have also been in a 3-year downtrend. What does all this mean? It means that the labor market is relatively balanced today after a lengthy period where workers had their choice of jobs and wage growth accelerated rapidly. The JOLTS report has been suggesting a slow and steady normalization of labor market conditions for a while and I think this is a fairly accurate take. As for what that means for Friday’s non-farm payroll report is unclear. These two reports often have little correlation with each other, although NFP is expected to show some moderation in December as well. All told, the jobs market has normalized although we have to see any major signs of an impending breakdown.

The services PMI report was the other major economic data point of note this week. It topped expectations last month and moved up to 54.1, indicating that the services sector in the U.S. is still in healthy expansion. The rates market, however, wasn’t as enthused. Stronger economic numbers have been hawkish for the Fed and the latest readings have pushed 2025 forecasts to just 1-2 rate cuts this year (with a lean towards just one). The 10-year is also threatening to touch its highest level since October 2023. The markets seem to be in this place where they’re satisfied that the U.S. economy is still in a good place, the Fed won’t be doing much to bring rates lower over the next 12 months and inflation risk is on the rise. All of this is helping to push yields higher where they might stay for a while. High yield spreads, while they’ve been gently moving higher in recent weeks, aren’t yet indicating any major stress in the junk bond space.

The story in Europe, as it is in many other corners of the world, is inflation. In the Eurozone, the December annualized inflation rate hit 2.4%. While that doesn’t seem like cause for concern on the surface, it’s risen significantly from the 1.7% print in September. Core inflation seems to have stabilized, which is a good sign, but it could limit what the ECB might do in 2025 should this trend continue. The central bank has already indicated its intentions to try to be more aggressive in order to address growth problems, but a persistent rise might cause them to tap the brakes a bit. There are, however, going to be some high base effects rolling off the calculation in the next several months and the shorter-term annualized rate is still running in the 1-2% range, so it’s possible the ECB can still proceed as planned.

Germany, however, is looking a little more ominous. Its inflation rate climbed to 2.6%, its highest reading since January 2024, while the core inflation rate moved above 3% for the first time since March. This comes at a rough time for an economy that’s been virtually stagnant for nearly three years. German bund yields have risen to their highest level since July and, as Europe’s largest economy, it’s unlikely we’ll see a recovery in the Eurozone without a reversal from Germany. It seems more and more likely that stagflation is becoming a significant risk in Europe.

The Japanese 10-year bond yield this past week hit 1.13%, which marks its highest level since 2011, after hitting 0.58% roughly one year ago. Given its continued struggles with growth, this is a fairly clear sign that inflation risk is on the rise in Japan. The inflation rate has been hovering around the 3% level for about a year, even as the yen continues to weaken. The BoJ took a pretty neutral policy stance at the December meeting, but I don’t think they’re going to have that luxury later this month. Conditions are pretty steadily moving against them, both on the inflation front and the forex market, and I think they might be forced to hike in two weeks whether they’re ready to or not. Prepare for more yen carry trade unwind risk.

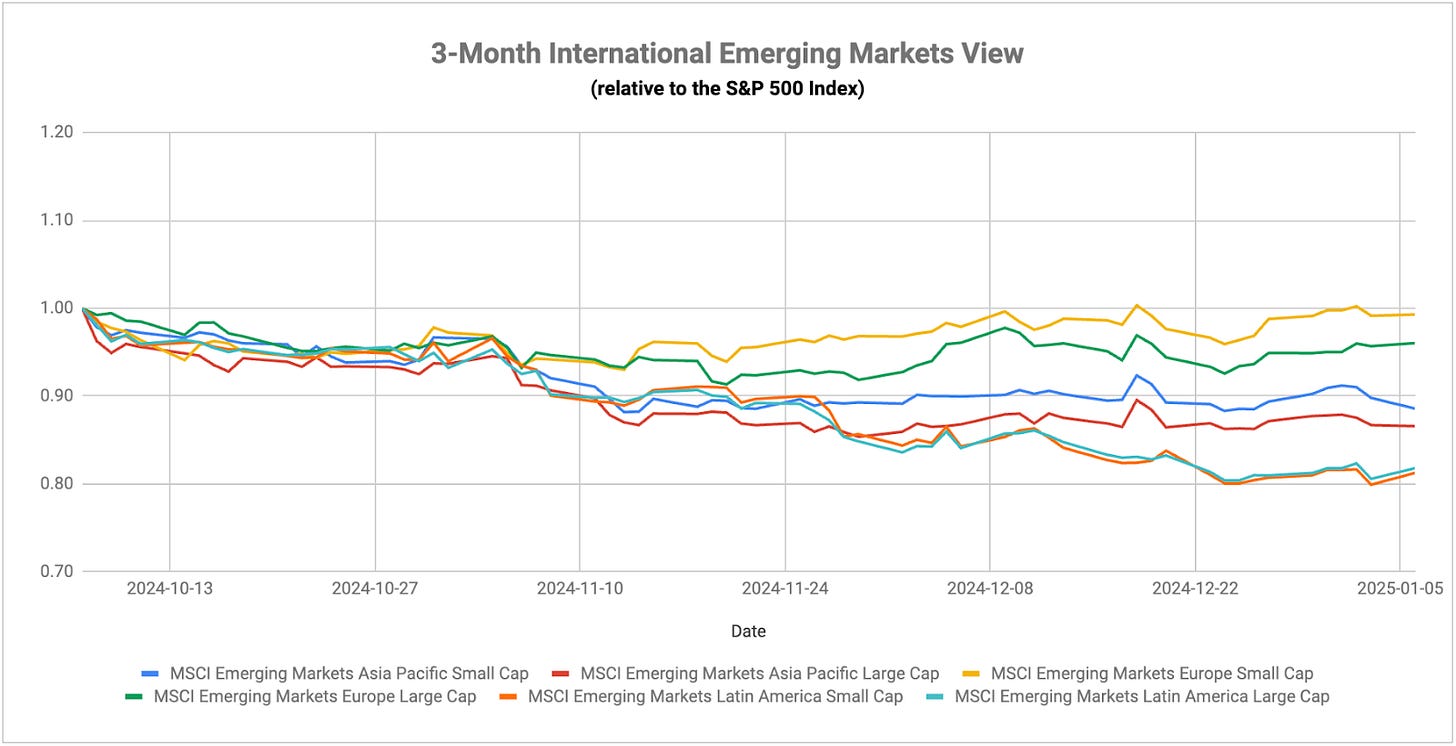

Without any type of major stimulus package coming to the rescue for now, China remains one of the biggest trouble spots in emerging markets. The real estate market is still in a state of serious distress with no major signs of an organic rebound in sight. Chinese consumer demand is still incredibly weak. Without a rebound there, it’s tough to imagine a sustainable recovery scenario. Most stimulative measures to date have centered around lower rates and rescuing bad debt, something that’s not really going to help consumers directly. I’d expect GDP growth in 2025 to come in shallow again unless the Chinese government issues some type of stimulus directly to consumers and does it relatively quickly. Demand is low because liquidity is low. Solve one and you probably solve the other. It feels like a stimulus announcement might come with little warning and unknown timing, so investing in China ahead of it might be a pure gamble more than anything. But it seems like China is likely to continue struggling until that stimulus package comes.

India, viewed by many as one of the go-to emerging markets over the past year or more, is showing signs of coming back down to earth. The country’s fiscal year-end GDP growth rate is expected to decline to 6.4%, which would be its slowest since the COVID pandemic. The larger problem now is that the country’s inflation rate is starting to hover around 6%, the very top end of the range that the Indian central bank typically prefers to see it. The RBI has kept its benchmark rate at 6.5% for the past two years in order to try to keep inflation contained, but it looks like rate hikes can’t be ruled out in 2025 in an environment where global central banks are favoring cuts. Indian stocks have performed OK over the past 12 months, but the need to raise rates could push them to underperformer status in the new year.

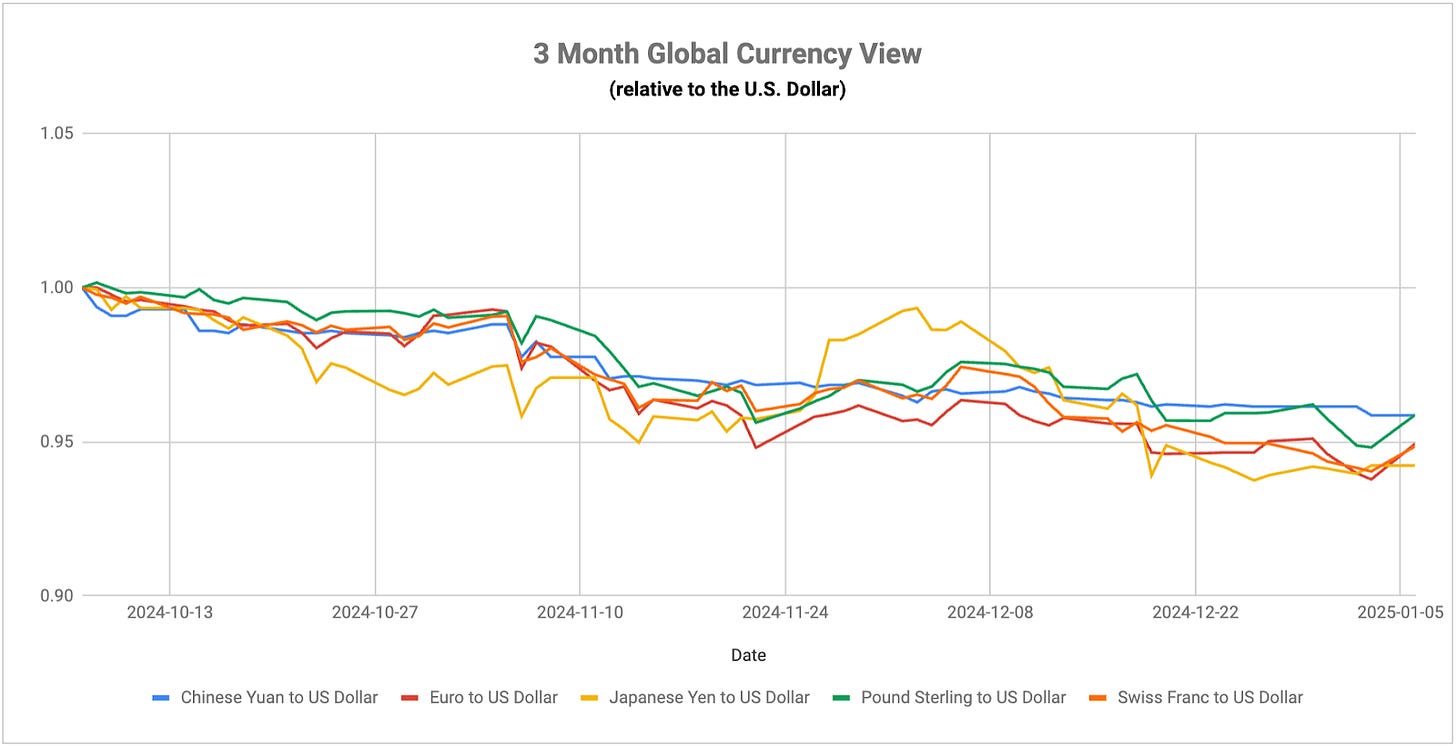

Outside of a bout of volatility on Monday surrounding the Trump tariff news, the dollar index has been on a nearly uninterrupted uptrend since late September. An unwind of Fed rate cut expectations and a trend of modestly higher inflation have pushed interest rates and the dollar higher. The inflation dynamic is happening elsewhere around the world, including Europe and Japan, also pushing long end yields higher. That’s helped to moderate some of the dollar strength in recent weeks, but the dollar still appears to be the currency of choice here.

The yen is back to 158, essentially the same level it was at before the BoJ’s rate hike and the big yen carry trade unwind. The country’s finance minister came out and said that he was concerned about some of the gyrations in the forex market, an apparent indication that the government is prepared to take measures to strengthen it. While it’s still up in there, I believe that the BoJ has to at least strongly consider a rate hike later this month or lay the groundwork for a hike sometime very soon. Japan’s growth rate isn’t at the level that they’d probably prefer, but a new era of stagflation would be even worse.