Every December, the same question resurfaces on Wall Street: will the market end the year with a seasonal gift, or deliver a lump of coal? The so-called “Santa Claus rally” has become one of the most enduring patterns in market history. Far from a holiday cliché, it reflects a persistent tendency for equities to strengthen during the final stretch of the calendar year, particularly in the last two weeks of December.

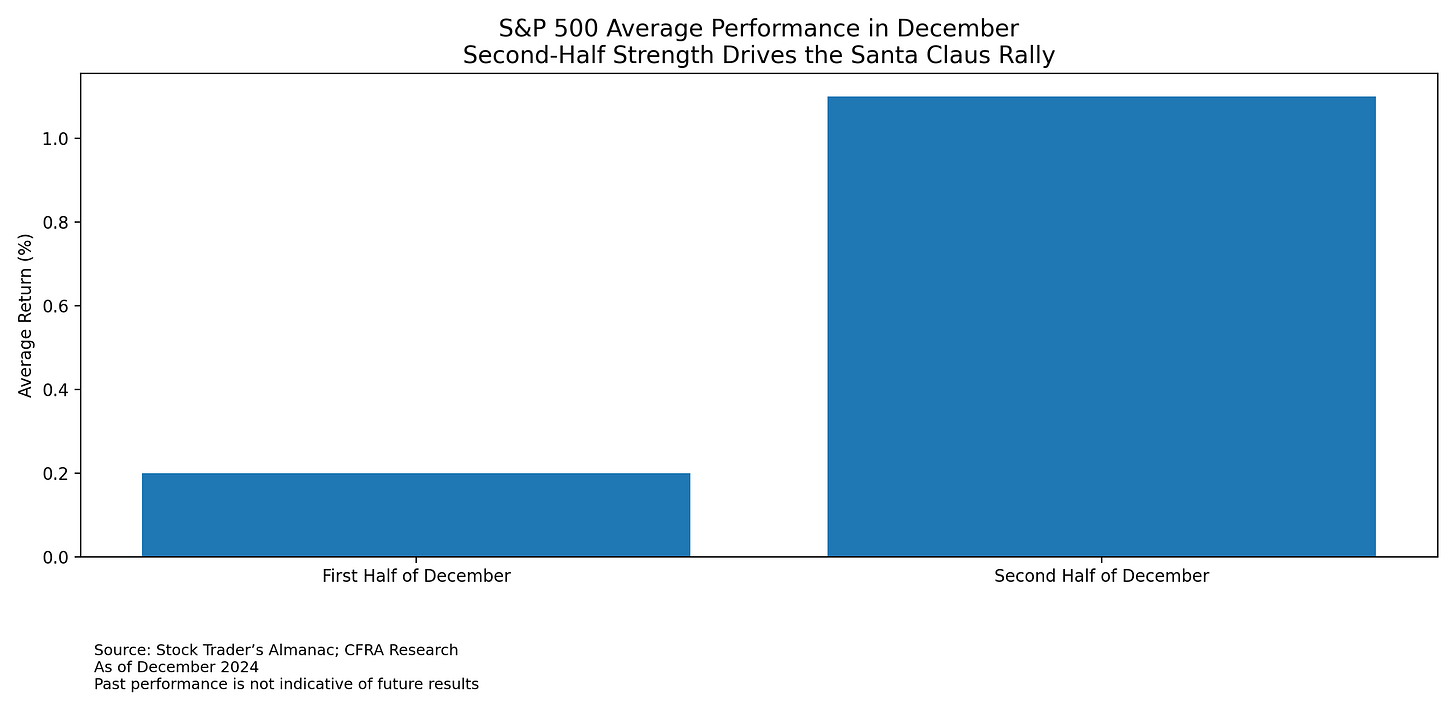

Over long market cycles, December has ranked among the stronger months for U.S. equities, with gains clustering disproportionately late in the month. Since the mid-twentieth century, the S&P 500 has finished December higher in roughly three-quarters of all years, and a significant share of those advances has occurred during the month’s closing weeks.¹ This concentration of strength has made late December one of the most consistently positive short windows on the market calendar.

That reliability has elevated the Santa Claus rally from statistical curiosity to sentiment gauge. When the rally appears, it often reinforces confidence heading into the new year. When it fails, investors tend to take notice.

A Seasonal Pattern With Staying Power

The Santa Claus rally was formally defined in the early 1970s by market historian Yale Hirsch as the final five trading days of December and the first two trading days of January.² Despite spanning just seven sessions, that window has historically produced gains far more often than losses. Since the mid-1940s, the market has finished that period higher roughly three-quarters of the time, an unusually high success rate for such a narrow slice of the calendar.³

This tendency has earned a place in market folklore, captured by Hirsch’s well-known rhyme: “If Santa Claus should fail to call, bears may come to Broad and Wall.” The message is not mystical. Instead, it reflects a recurring observation that weak year-end performance can signal deteriorating investor confidence beneath the surface.

History offers several examples. The absence of a Santa rally heading into 2000 and 2008 preceded two of the most severe bear markets in modern history.⁴ More recently, a muted year-end advance in late 2015 was followed by heightened volatility and a difficult start to 2016. These episodes do not imply causation, but they reinforce the idea that late-December performance often reflects prevailing risk appetite.

Seasonality does not override fundamentals, but it does shape probabilities. November and December together have formed a durable pocket of strength across multiple economic regimes, monetary cycles, and political environments.⁵ The persistence of the pattern suggests that structural and behavioral forces, rather than chance, are at work.

Why Late December Tends to Favor Stocks

Several factors converge as the year draws to a close. Investor psychology plays a central role. The holiday season often coincides with improved sentiment, lighter news flow, and a collective inclination to look ahead rather than dwell on recent setbacks. That shift alone can influence short-term market behavior.