Key Highlights

The surge in metals prices looks less like a return to 1970s-style inflation and more like a late-cycle speculative blowoff.

Parabolic moves in silver, copper, and uranium resemble prior manias where valid long-term themes were priced far too quickly.

True inflation is broad and persistent; today’s commodity strength is narrow and increasingly driven by positioning and narrative momentum.

Economic signals beneath the surface point toward slowdown risks that historically precede deflationary shocks, not inflation spirals.

History suggests the greatest opportunities in secular themes often emerge after speculative excess unwinds, not before.

At first glance, the surge across precious and industrial metals looks like a throwback to the inflationary 1970s. Silver and platinum pushed to record highs late in 2025, while gold posted its strongest annual gain since the Carter era.¹ To many investors, the message appears straightforward: fiat credibility is eroding, central banks are poised to ease, and hard assets are reasserting their monetary role.

That conclusion, however, mistakes price action for macro reality. Not every commodity boom signals inflation. Some mark the final, speculative phase of a cycle already nearing exhaustion.

The defining feature of today’s metals rally is not broad-based price pressure across the economy. It is concentration. Capital is flooding into a narrow set of assets tied to electrification, clean energy, and geopolitical supply fears. These rallies feel less like a replay of the 1970s and more like the late stages of a speculative build-out, where narratives outrun near-term economic capacity to absorb them.

Precious Metals and the Illusion of Inflation

Silver’s explosive move has been widely justified by structural supply deficits and its growing role as a critical industrial input. That argument contains truth, yet it fails to explain the speed of the advance. Structural shifts rarely justify parabolic price action in months rather than years. When prices behave that way, positioning and sentiment usually matter more than fundamentals.

Gold’s rally tells a similar story. Its rise has been fueled by a weaker dollar, geopolitical uncertainty, and expectations of future rate cuts. Those are cyclical tailwinds, not proof of a sustained inflation regime. In prior true inflationary cycles, rising prices were accompanied by accelerating wages, persistent cost-push pressures, and widespread demand destruction. Today, many goods prices are stable or falling, while growth momentum is slowing beneath the surface.

What looks like inflation hedging increasingly resembles capital crowding into perceived “safe” narratives at a late stage of the cycle.

Copper, Uranium, and the Echo of 1999

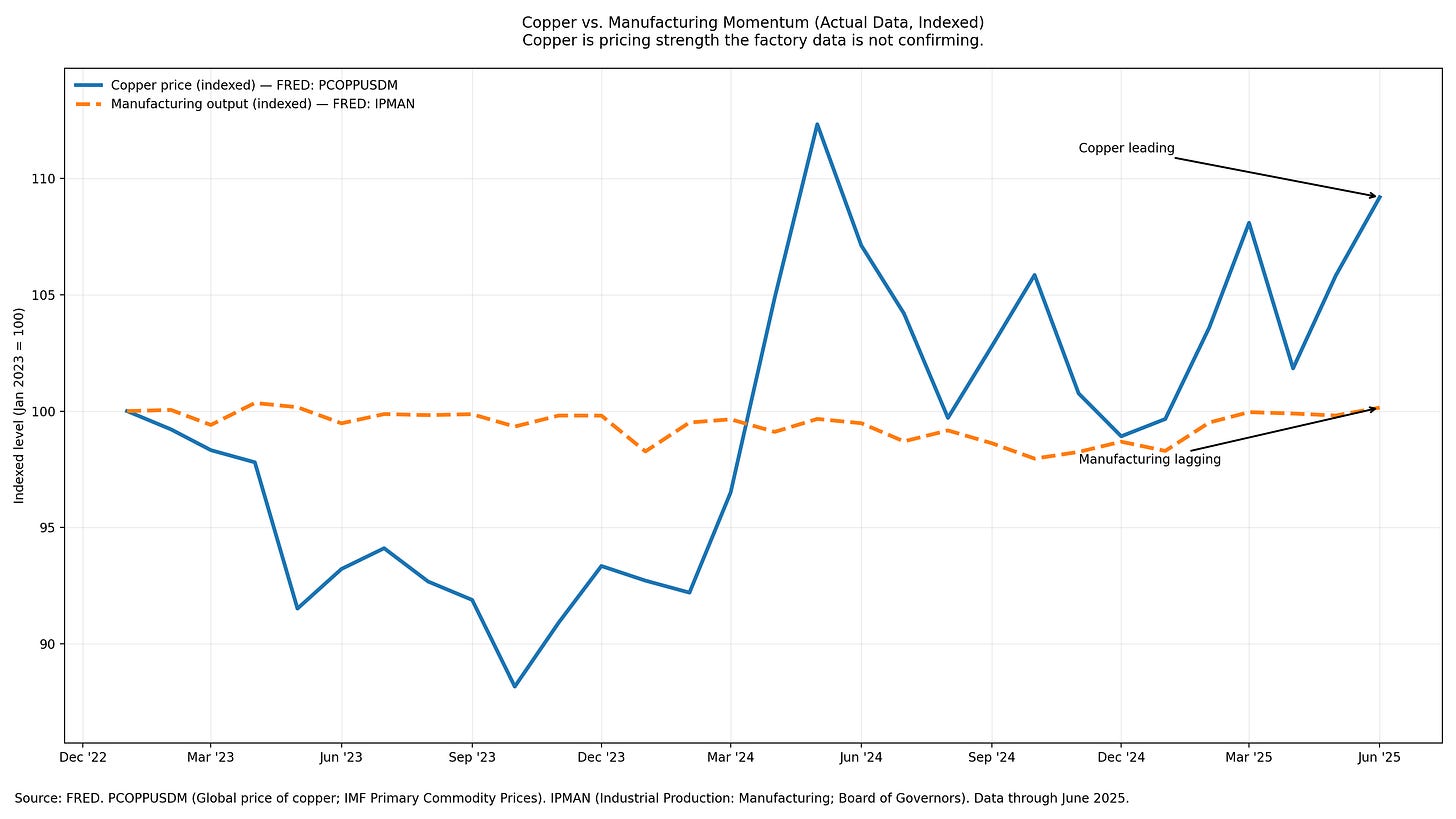

Copper is often called the metal with a PhD in economics, yet its recent behavior has looked more like a momentum trade. Prices surged to new highs on expectations tied to renewable energy, electric vehicles, and AI-driven infrastructure demand.² Those themes are real. The extrapolation is not.

In late 2025, copper prices swung sharply on profit-taking linked not to physical demand, but to volatility in technology stocks.³ When a base metal trades off sentiment surrounding equity speculation, it signals that fast money has entered the trade. Fundamentals may justify higher prices over time, but they rarely explain vertical moves absent speculative leverage.

Uranium provides the clearest parallel. After years of underinvestment, supply constraints have collided with renewed enthusiasm for nuclear power. Utilities have rushed to secure long-term contracts, while financial vehicles have absorbed physical supply.⁴ These dynamics are legitimate, yet the speed and intensity of the rally recall prior commodity manias.

The last major uranium spike in 2007 ended badly, despite a similarly compelling narrative. Prices collapsed once demand expectations proved too optimistic relative to the pace of reactor build-outs. The current “nuclear renaissance” may ultimately be real, but markets are once again pricing the end state long before the transition can be realized.

The Fiber-Optic Parallel

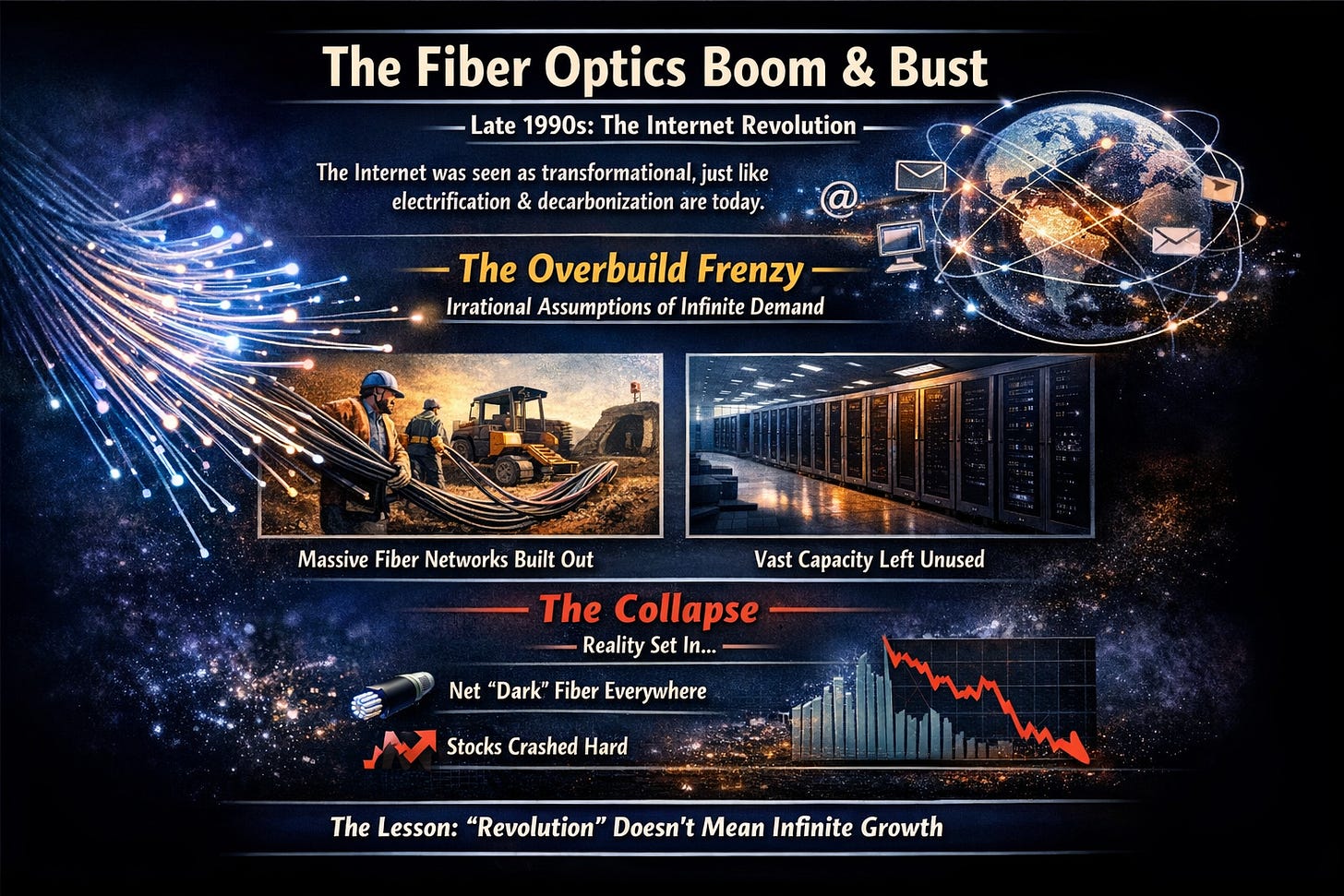

The late 1990s offer a useful analogy. The internet was transformational, just as electrification and decarbonization are today. That did not prevent investors from massively overbuilding fiber-optic networks based on assumptions of infinite demand. When the cycle turned, the majority of that infrastructure sat unused, and the stocks tied to it collapsed.⁵

Today’s metals complex shows similar characteristics. Prices are moving as if future demand has already arrived in full. Capital spending plans, policy goals, and long-term aspirations are being treated as immediate consumption. That disconnect is where bubbles form.

Inflation Versus Speculation

True inflation is broad, persistent, and self-reinforcing. The 1970s oil shocks rippled through every sector of the economy, driving sustained increases in wages and living costs.⁶ Today’s environment looks very different. Outside of select services, pricing power is fading. Growth indicators are rolling over, and financial conditions remain restrictive.

China, the world’s largest commodity consumer, continues to struggle with property-sector weakness and uneven industrial demand.³ In the United States, deeply inverted yield curves have historically preceded economic downturns, not inflationary booms. Markets are receiving conflicting signals, and history suggests the real economy usually wins.

The risk is that today’s commodity strength represents the final expression of excess liquidity and narrative momentum before demand softens meaningfully. That pattern played out in 2008, when oil surged to record highs only to collapse as the global economy entered crisis.⁷ What began as an inflation scare ended as a deflationary shock.

Positioning Matters More Than Narratives

Markets rarely punish investors for being early on secular themes. They punish investors for paying too much, too late. The current metals boom shows many hallmarks of over-positioning: extreme forecasts, crowded trades, and volatility driven by sentiment rather than consumption.

This does not invalidate the long-term case for copper, uranium, or precious metals. It reframes the timing risk. Secular demand growth does not move in straight lines, and late-cycle enthusiasm often creates better opportunities after the unwind.

Even gold, often treated as immune to deflationary shocks, fell sharply during the 2008 crisis before resuming its longer-term uptrend. Liquidity events do not discriminate. They force selling where leverage and crowding are highest.

Preparing for the Other Outcome

If the consensus is positioned for sustained inflation, the asymmetric risk lies in deflation. A global slowdown, financial accident, or policy misstep could quickly reverse the forces driving today’s rallies. In that scenario, assets perceived as “stores of value” can behave very differently than expected.

The prudent response is not panic or blanket liquidation. It is discipline. Investors should reassess assumptions embedded in parabolic price moves and consider whether they are being compensated for downside risk. Cycles do not end when narratives peak, but they often end soon after.

The metals boom increasingly resembles a speculative finale rather than the start of a new inflationary era. History rarely repeats, but it often rhymes. The current rhyme sounds closer to 1999 or 2008 than to 1973.

Recognizing that distinction may prove far more valuable than chasing the next headline-driven surge.

Footnotes

Sarah Qureshi, “Silver Crosses $77 Mark While Gold, Platinum Stretch Record Highs,” Reuters, December 26, 2025.

Tom Daly, “Copper Nears Record High as Supply Tightness Back in Focus,” Reuters, December 19, 2025.

Reuters, “Copper Prices Rise on Weaker Dollar, Ignoring Weak China Data for Now,” December 15, 2025.

Muflih Hidayat, “The Rising Tide: Why Uranium Prices Are Surging in 2025,” Discovery Alert, October 3, 2025.

Mathew Ingram, “Sometimes Bubbles Can Be Good,” The Torment Nexus, November 2023.

William Poole, “Volcker’s Handling of the Great Inflation Taught Us Much,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Regional Economist, January 2005.

“Price of Oil – 2008 Oil Price Shock,” Wikipedia, citing historical WTI data.

The Lead-Lag Report is provided by Lead-Lag Publishing, LLC. All opinions and views mentioned in this report constitute our judgments as of the date of writing and are subject to change at any time. Information within this material is not intended to be used as a primary basis for investment decisions and should also not be construed as advice meeting the particular investment needs of any individual investor. Trading signals produced by the Lead-Lag Report are independent of other services provided by Lead-Lag Publishing, LLC or its affiliates, and positioning of accounts under their management may differ. Please remember that investing involves risk, including loss of principal, and past performance may not be indicative of future results. Lead-Lag Publishing, LLC, its members, officers, directors and employees expressly disclaim all liability in respect to actions taken based on any or all of the information on this writing.