Key Highlights

Large-cap value appears to have bottomed against large-cap growth, ending a multi-year stretch of relative underperformance and signaling a potential shift in market leadership.

Valuation extremes favor value stocks, with discounts versus growth near historically rare levels, increasing the odds of sustained mean reversion if expectations for mega-cap growth moderate.

Easing monetary policy historically supports value leadership, particularly when rate cuts occur without a recession, as economically sensitive sectors respond to improving financial conditions.

A value-led market typically broadens participation, creating tailwinds for small-cap stocks and international equities that have lagged U.S. large-cap growth for years.

Risk-on may increasingly be expressed outside of technology, with leadership rotating toward health care, financials, industrials, and overseas markets rather than Nasdaq-heavy exposures.

Portfolio concentration risk rises when leadership narrows, making diversification across styles, regions, and market capitalizations more important as the market regime evolves.

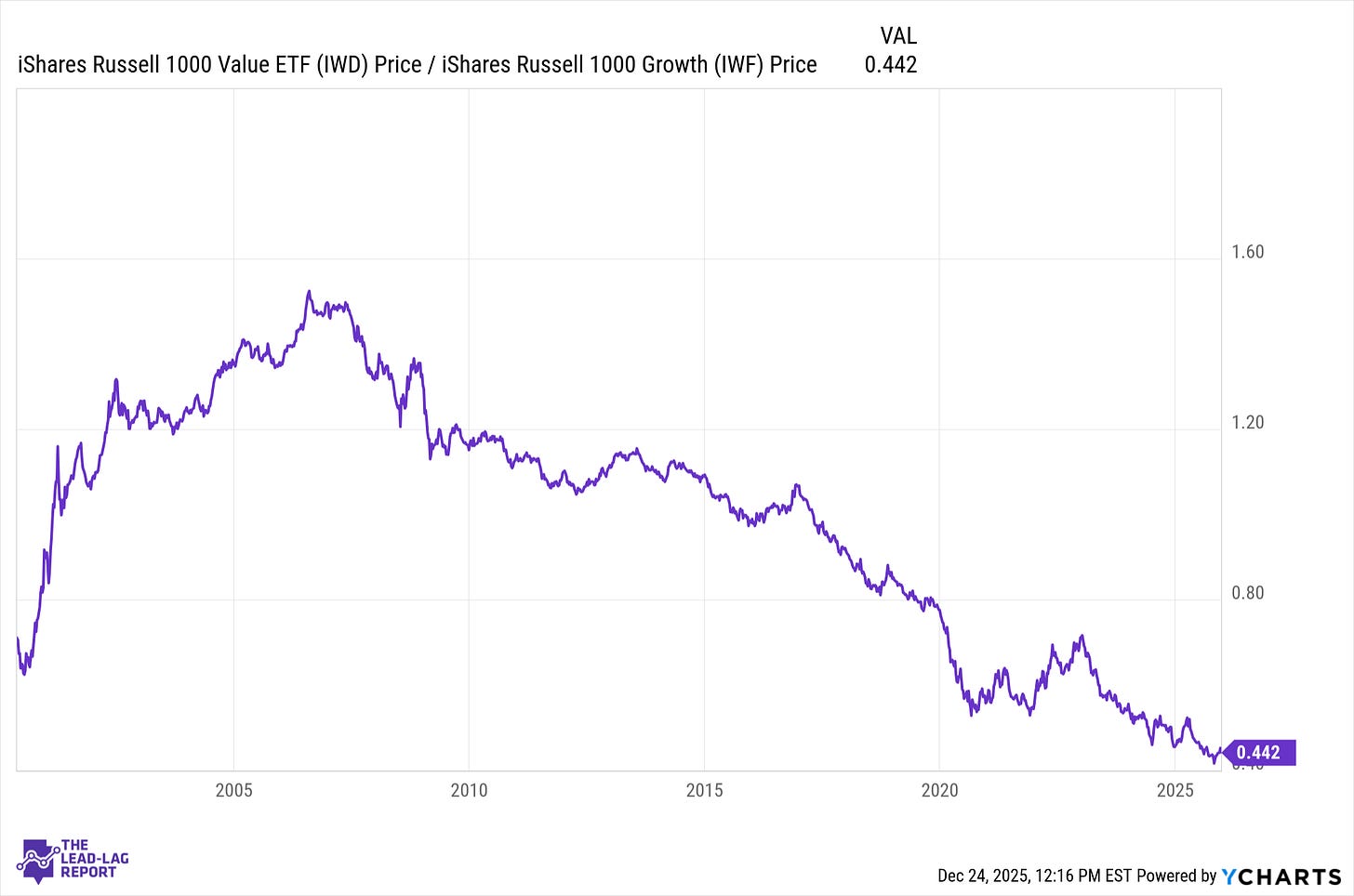

For much of the past decade, investing success has felt increasingly narrow. Large-cap growth stocks, led by a small group of dominant technology firms, captured a disproportionate share of market gains, while value stocks consistently lagged. That imbalance shaped investor behavior, portfolio construction, and even perceptions of what “risk-on” meant in equity markets. Recently, however, evidence has begun to accumulate that this long-standing leadership may be changing. After years of underperformance, large-cap value appears to have bottomed relative to growth, a shift that could carry broader implications across asset classes and regions.¹

A Decade of Growth Dominance Meets Its Limits

Since the global financial crisis, growth stocks benefited from an unusually favorable backdrop. Persistently low interest rates supported higher valuations, while technological innovation concentrated profits among a small group of mega-cap firms. By the early 2020s, enthusiasm around artificial intelligence further amplified this dynamic, pushing growth indices to historically concentrated levels. At one point, a handful of stocks accounted for more than 40 percent of global growth benchmarks.¹

Value stocks, by contrast, spent much of this period on the sidelines. Traditional value sectors such as financials, industrials, and energy struggled with slower growth, regulatory pressure, and shifting investor preferences. As a result, value lagged growth for most of the past two decades, reinforcing the perception that its style was structurally disadvantaged.²

That narrative may now be fraying. The relative performance of large-cap value versus large-cap growth appears to have reached a trough in late 2025 and has since turned higher. In practical terms, value stocks have begun to outperform growth following an extended drawdown. Market leadership late in the year reflected this shift, as several high-profile growth names stalled while previously overlooked value sectors gained traction.³

Valuations and Policy Create a Different Setup

One reason the recent turn matters is how extreme the valuation gap had become. By late 2024, value stocks were trading at discounts to growth that exceeded long-term norms by a wide margin. On normalized earnings measures, the discount reached levels rarely seen outside major regime shifts.¹ Such extremes tend to coincide with inflection points, particularly when investor expectations for growth stocks are elevated.

At the same time, macroeconomic conditions have begun to evolve. After an aggressive tightening cycle, central banks are shifting toward easier policy as inflation pressures moderate. Historically, the period following the first rate cut in a cycle has often favored value stocks, provided the economy avoids recession.¹ Lower borrowing costs tend to benefit cyclical industries and balance-sheet-sensitive businesses, many of which reside in value indices.

This does not imply that growth companies lose their relevance or profitability. Instead, it suggests that much of their expected success may already be reflected in prices. As expectations rise, the margin for disappointment narrows. Value stocks, by contrast, enter this phase with lower expectations and greater valuation support, creating asymmetric upside if economic conditions stabilize.¹

Broader Market Implications: Size and Geography

Shifts in value leadership rarely occur in isolation. Historically, periods of value outperformance have often coincided with stronger performance from smaller companies and non-U.S. markets. Recent data hint at a similar pattern emerging.