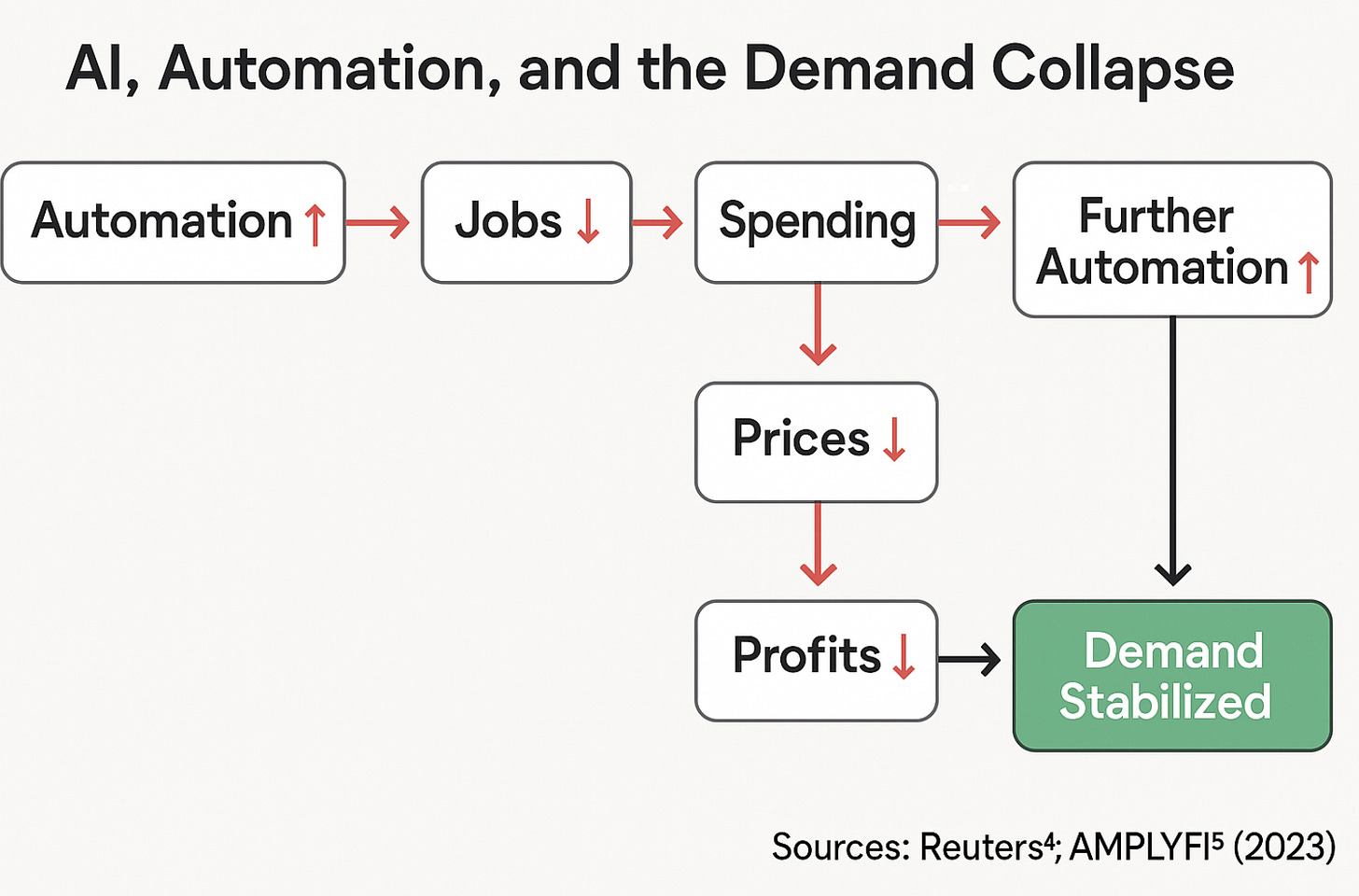

Capitalism depends on consumer spending, not ideology. About 70 percent of U.S. GDP has long come from household consumption¹. The system runs on a simple feedback loop: businesses pay workers, who then buy the goods and services those same businesses sell². As automation accelerates, that loop is breaking. Artificial intelligence can generate enormous productivity, but if machines replace enough workers, who remains to purchase the output? Some economists warn of a “terminal paradox”: abundance without income to buy it².

The risk is a deflationary doom loop—AI cuts labor costs, wages shrink, spending falls, and companies cut costs again³. Without wage income, demand collapses and the capitalist engine seizes. This isn’t theoretical. Goldman Sachs estimates that 18 percent of jobs worldwide could be automated, with roughly 7 percent of U.S. workers displaced, particularly in white-collar roles⁴. When incomes vanish, consumption weakens and deflation looms. As one futurist noted, mass unemployment would “crush consumer spending,” creating overproduction and persistent price declines⁵. For central bankers, deflation is the ultimate nightmare: it freezes demand and traps economies in stagnation.

UBI: Maintenance, Not Charity

When wages can no longer sustain consumption, the system must invent a substitute. Universal Basic Income (UBI) provides that substitute—not as charity, but as maintenance. A government-funded income floor would replace lost paychecks, ensuring citizens still have cash to spend and businesses still have customers. UBI keeps the market engine lubricated.

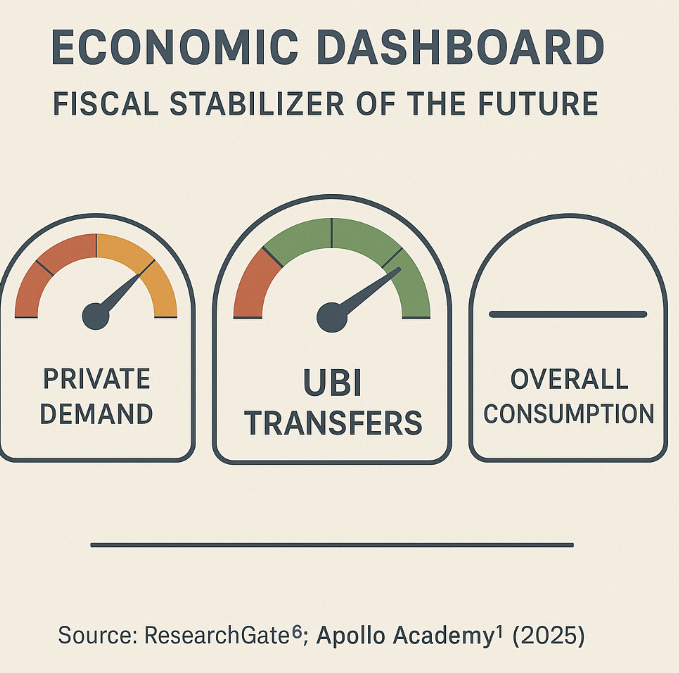

Economists have likened UBI to a permanent “automatic stabilizer.” Like monetary stimulus, it would inject purchasing power directly into households whenever private demand falters⁶. During recessions or tech-driven layoffs, payments would flow automatically—no congressional bargaining, no central-bank improvisation. Keynesian logic supports the approach: a baseline of income preserves a baseline of demand.

The goal is self-preservation, not altruism. In effect, capitalism would be paying itself an allowance to survive. Even leading technologists concede the point. Elon Musk has said that as AI performs most human labor, “probably none of us will have a job,” predicting a world of “universal high income” sustained by automation⁷. Venture capitalist Vinod Khosla similarly argues that as AI reduces labor needs, “UBI could become crucial” to channel the wealth created by machines back to consumers⁸. Their conclusion is pragmatic: without a broad income floor, capitalism risks implosion from its own efficiency.

An economy with UBI could resemble a subscription model: the state funds citizens, who in turn subscribe to the output of automated industries. The loop sustains itself—AI boosts productivity, displaces jobs, triggers UBI transfers, which then finance purchases of AI-produced goods, which generate profits taxed to fund the next round of stipends. Rather than one-off stimulus, UBI becomes a continuous circuit preventing the economy from stalling when the wage–spending link breaks. It acts as a pressure valve, releasing the economic tension that would otherwise explode in mass unemployment and social unrest.

The New Automatic Stabilizer

From a macroeconomic perspective, UBI could become the defining automatic stabilizer of the twenty-first century. Like Social Security or unemployment insurance, it would cushion recessions but operate constantly and universally. When downturns hit, stipends would prevent household spending from vanishing; during booms, the steady flow might reduce the need for debt-fueled excess. UBI is essentially “helicopter money” on autopilot.

Because it is unconditional, it avoids bureaucratic delay. One analysis notes that UBI could “immediately inject purchasing power into households” during recessions⁶. In plain terms, it keeps wallets open when jobs close. Politically, it may prove more durable than corporate bailouts or quantitative easing, which often stoke resentment for favoring Wall Street over Main Street. A universal transfer, by contrast, directly benefits everyone, giving it broader legitimacy.

Over time, policymakers could use UBI adjustments the way central bankers once used interest rates—raising payments in downturns, trimming them when inflation rises. Fiscal and monetary policy would blur: the Treasury would perform the stabilizing role once reserved for central banks, channeling liquidity through citizens rather than bond markets. UBI, then, becomes not a radical idea but fiscal infrastructure—a built-in circuit breaker against deflation and political instability.